The Investor Playbook for Trade War 2.0

A deep-dive analysis of the ongoing 2025 trade war, with sector-specific insights and macroeconomic implications.

Trade policies don’t always make headlines, but when they do, it’s usually because they’re creating disruptions. With tariffs expanding and global trade relationships shifting, the current landscape demands a closer look. Recent developments have introduced significant uncertainties for businesses, investors, and policymakers, and I felt it was important to provide a clear and structured analysis of what’s happening.

This overview breaks down the key developments in the escalating trade conflict under President Trump’s second term, commonly referred to as “Trade War 2.0” (2025-present). I’ll also compare them to the 2018-2020 trade war and assess their implications for global economies and investment landscapes. My intent is to offer a clear and professional perspective on these events, similar to the discussions we might have during a consultation—focusing on the broader economic picture, rather than specific investment recommendations or performance data.

One caveat: Given the rapid pace of developments—changing daily and even hourly—it’s impossible to have the most up-to-date information at any single moment, but this analysis provides a structured framework to navigate the unfolding landscape.

Introduction: The Dawn of Trade War 2.0

After taking office in January 2025 for a second term, President Trump wasted little time in reviving and expanding the trade war agenda. Unlike the more targeted tariffs of 2018-2020 (focused mainly on China), this new round of trade confrontation is broader in scope, affecting multiple countries and industries at once. Trump himself acknowledged that Americans might feel “some pain” from higher prices due to tariffs, but argued it is the price to pay for achieving U.S. policy goals.

What’s different this time? In Trade War 2.0, the scale and coverage of tariffs have widened dramatically. During Trump’s first term, tariffs mostly hit specific categories (like steel, aluminum, and certain Chinese goods). Now, entire countries and broad sectors are in the crosshairs. For example, sweeping duties on all Chinese imports are being imposed, and new tariffs target allies and rivals alike. Retaliation from other nations has been swift as well, with China and others responding in-kind or adopting countermeasures. All of this is creating a more complex and unpredictable trade environment as we move through 2025.

Before diving into the current situation, let’s briefly recap the first trade war (2018-2020) to set the stage, and then we’ll focus on the present developments in detail.

Flashback: Trade War 1.0 (2018-2020)

Trade War 1.0 unfolded during Trump’s first term and primarily featured a U.S.-China tariff tit-for-tat. The U.S. imposed 10%, then 25% tariffs, on roughly $370 billion worth of Chinese exports over 2018-2019, citing unfair trade practices. China retaliated with tariffs of 5–10% on about $75 billion of U.S. goods, targeting products like soybeans, autos, and energy. American consumers and businesses effectively bore the cost of these tariffs through higher prices, even though the administration often claimed otherwise.

The first trade war’s economic impacts were noticeable but not catastrophic. U.S. importers shifted some supply chains from China to other countries (like Mexico, Vietnam) to dodge tariffs. Yet, the overall U.S. trade deficit kept growing and manufacturing job gains remained modest. Certain U.S. industries benefited – for instance, domestic steelmakers enjoyed tariff protection with a 25% duty on imported steel, allowing higher prices. But many of those gains proved temporary; some U.S. steel and aluminum plants that reopened in 2018 later idled again as global oversupply kept pressure on prices.

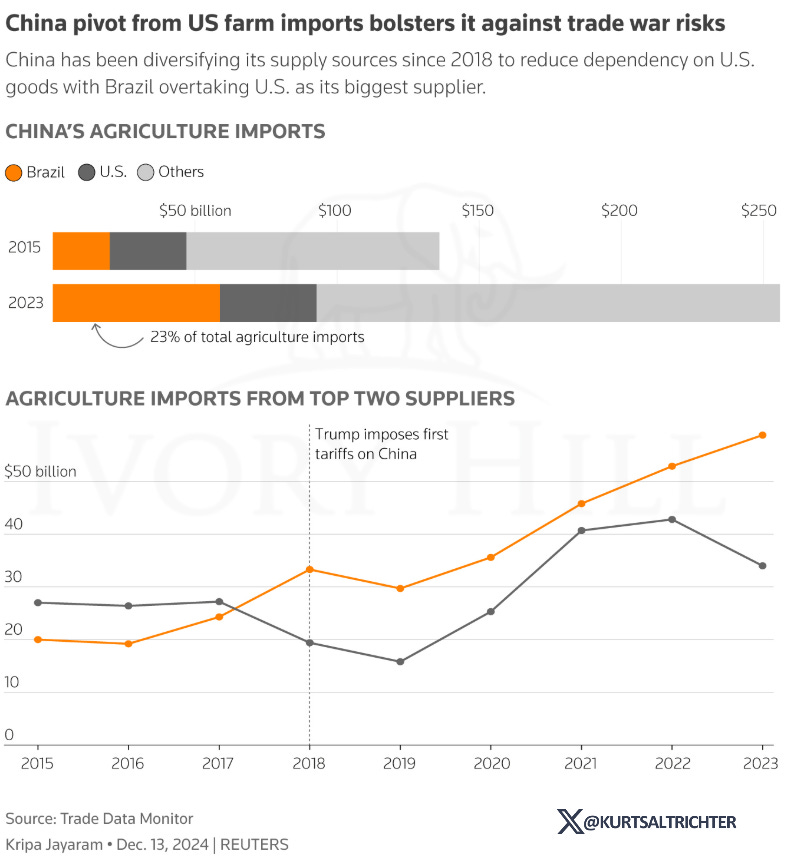

Meanwhile, American exporters in agriculture and aerospace were hit hard by retaliation. China slapped a 25% tariff on U.S. soybeans and sharply curtailed purchases of American soy, corn, and pork, turning to Brazil and others. U.S. soybean exports to China never fully recovered – Brazil permanently captured much of that market. China also shifted big-ticket purchases away from U.S. manufacturers; notably, Chinese airlines delayed or canceled orders from Boeing in favor of Europe’s Airbus. At one point, commercial aircraft had been the top U.S. export to China, but by 2020-2021 China’s orders for Boeing planes were minimal, a trend that has been slow to reverse.

Trade War 1.0 paused with the “Phase One” trade deal in Jan 2020, where China pledged to buy an additional $200 billion of U.S. goods and address some intellectual property and agricultural concerns. However, China ultimately fell short of those purchase targets (exacerbated by the pandemic). Many U.S. tariffs on Chinese goods remained in place through 2021-2024, but no further escalations occurred under President Biden, who maintained most tariffs but pursued a less confrontational tone.

This uneasy truce set the stage for Trade War 2.0. When Trump returned to office in 2025, he not only resumed hostilities towards China, but broadened the conflict to other trading partners, seeking to remake global trade on his terms. Let’s now explore the key developments of Trade War 2.0 to date.

Major Developments in Trade War 2.0 (2025-Present)

Under Trump’s renewed “America First” trade agenda, a series of sweeping tariff actions and policy moves have been rolled out in 2025. Below we summarize the most significant developments so far:

Across-the-Board U.S. Tariffs – 10% on All Imports: In one of the most dramatic policy shifts, President Trump has pledged to impose a universal 10% tariff on essentially all U.S. imports. This marks a sharp escalation from the targeted approach of the previous trade war. In fact, a 10% duty on everything the U.S. imports would affect over $2.8 trillion in goods (imports from all countries) – a massive intervention in global trade flows. By early February 2025, the U.S. did implement a 10% blanket tariff on Chinese imports specifically, signaling that the broader global tariff could follow. The goal, according to the administration, is to pressure trading partners across the board to negotiate “better deals,” although it means higher costs for U.S. businesses and consumers in the interim.

Tariffs on China – From 10% to 25%… and Threats of 60%: U.S.-China trade friction is the centerpiece of Trade War 2.0. In addition to the 10% across-the-board tariff on Chinese goods effective Feb 4, 2025, President Trump has threatened to ratchet duties up to 25%, 40%, even 60% on Chinese imports if China does not meet U.S. demands. This is an unprecedented level – for context, the highest tariff rate in the first trade war was 25%. A 60% tariff would dramatically raise prices on virtually all Chinese-made products in the U.S., from electronics to furniture. Even the rumor of such steep tariffs has unsettled markets and businesses, as it essentially signals a possible complete decoupling. While it remains a threat at this stage, economists put fairly high odds on significant escalation – Goldman Sachs estimated a 90% probability that sweeping new China tariffs will be implemented, and a Reuters poll of economists predicted tariffs could reach 40% in reality. In short, the U.S. is brandishing an economic “big stick” toward China.

Update as of March 4, 2025: The 10% tariff that Trump placed on Chinese imports in February was doubled to 20%.

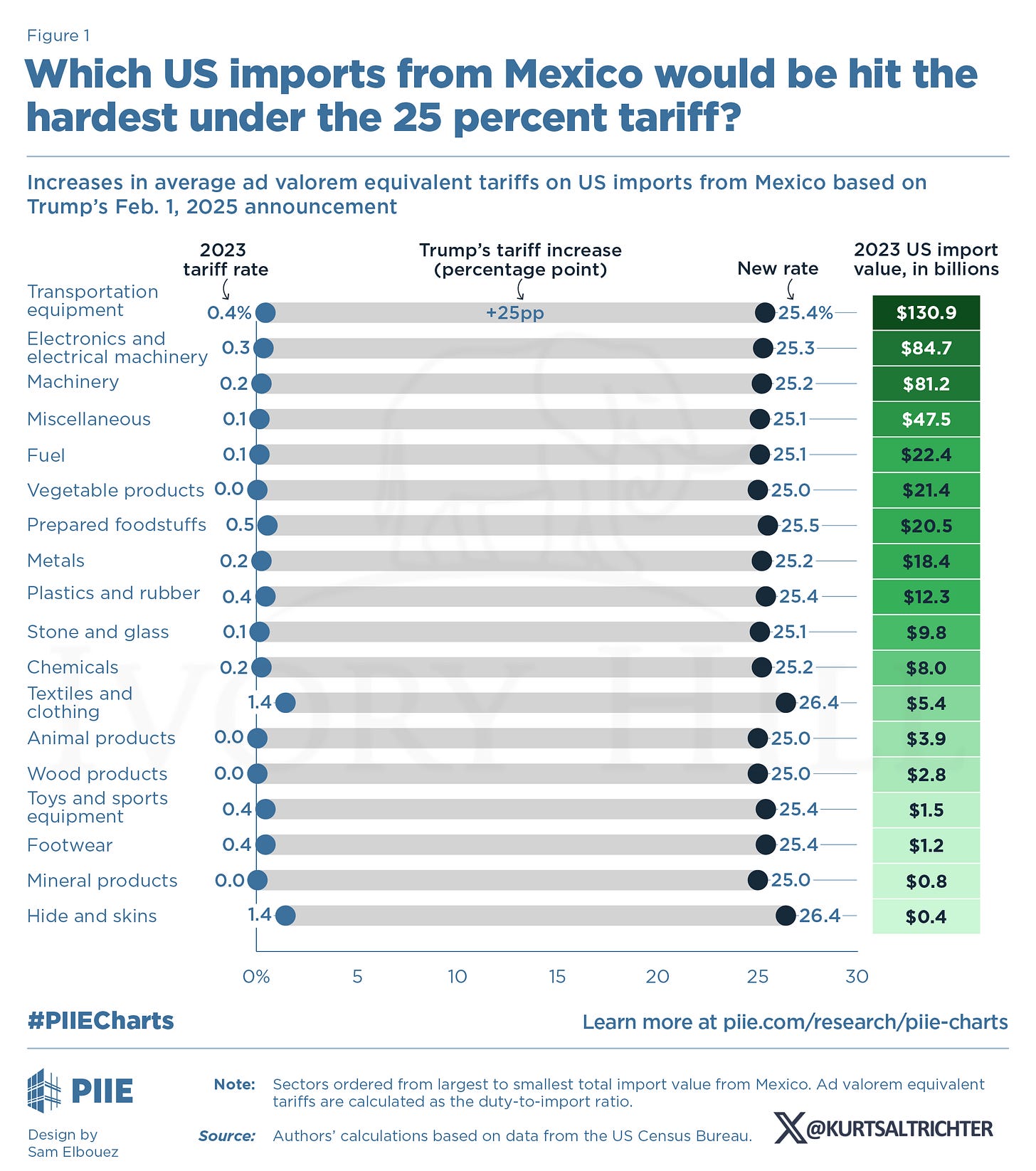

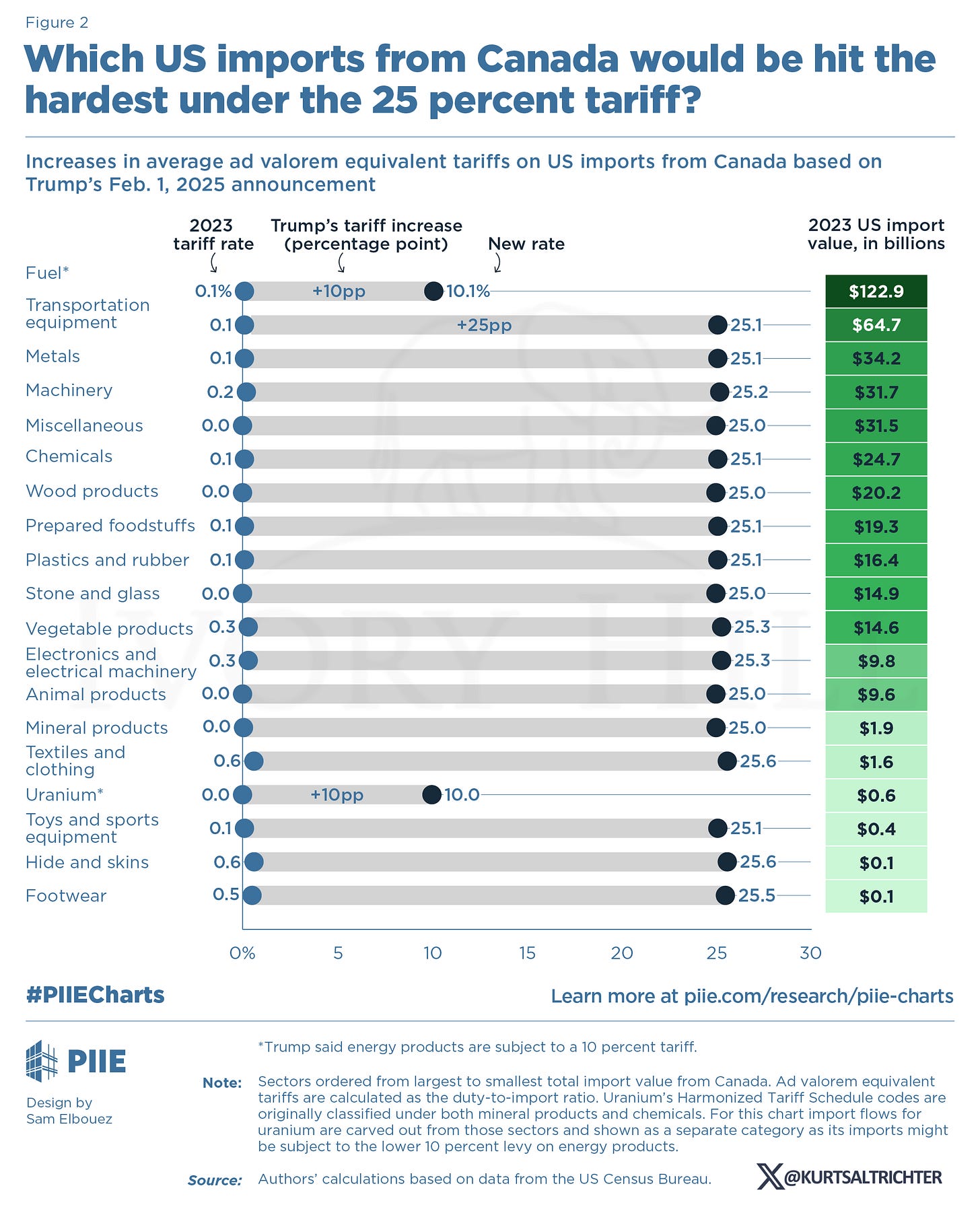

Tariffs on USMCA Partners (Canada & Mexico) – A Near Miss: In a controversial move, Trump also announced 25% tariffs on all imports from Canada and Mexico (America’s #1 and #2 trading partners) to take effect Feb 1, 2025. This shocked many, as it targeted close U.S. allies and risked major economic disruption in North America. After a tense standoff, the White House paused these tariffs for 30 days until March 2025 in exchange for concessions on U.S. border security concerns. Canada’s government, for example, agreed to reinforce efforts to curb the flow of fentanyl and illegal migrants, which was a key demand from Washington. Similarly, Mexico pledged stricter immigration enforcement (echoing a 2019 episode when Trump had threatened tariffs over border issues). The pause averted an immediate price spike on a huge range of goods – remember, Mexico is the U.S.’s largest source of imported food products (fruits, vegetables, avocados, etc.) and a major source of autos and auto parts. Had the 25% tariff hit in February, Americans would have seen sharp jumps in grocery prices and car prices within weeks. In fact, analysts warned a 25% Mexico tariff could raise U.S. new car prices by $2,100 on average (and up to $8,000-$10,000 for vehicles fully made in Canada/Mexico). That scenario is on hold, but not off the table – the Trump administration made clear that if Mexico/Canada don’t sufficiently address border issues, tariffs could be imposed later. This uncertainty is hanging over North American supply chains. (We’ll discuss the auto sector impact more in a later section.)

Update as of March 4, 2025: Starting just past midnight, imports from Canada and Mexico are now to be taxed at 25%, with Canadian energy products subject to 10% import duties.

“Fair and Reciprocal” Tariff Policy: The administration has launched a sweeping review aimed at equalizing tariffs and trade barriers with all U.S. trading partners. Trump signed a memorandum on Feb 13, 2025 directing officials to identify where other countries’ tariffs on U.S. goods are higher than U.S. tariffs on theirs, and to recommend reciprocal tariffs to level the field. In Trump’s view, many countries have “unfair” tariff rates – an often-cited example: the European Union charges a 10% tariff on imported American cars, while the U.S. only charges 2.5% on European cars. The plan is to raise U.S. tariffs to match foreign rates unless those countries lower theirs. For instance, U.S. auto import tariffs on EU cars could jump from 2.5% to 10% to mirror the EU’s rate. Similar adjustments could target Japan, India, and others that have higher import duties on certain U.S. goods. This “Tariff Reciprocity” policy is still under study – Trump gave his Cabinet until August 2025 to report on potential reciprocal tariffs – but if implemented widely, it means new tariffs on a broad set of countries beyond just China. U.S. allies in Europe and Asia are understandably uneasy and have been proactively negotiating to avoid being hit. We may see some bilateral deals or concessions emerge (for example, the EU is discussing lowering its auto tariff or other trade barriers to appease Washington). In any case, the message is that no country is exempt from the new hardball U.S. trade stance.

Global Metals Tariffs Reinstated (and Increased): Back in 2018, Trump imposed 25% tariffs on imported steel and 10% on aluminum globally, but later exempted or replaced those with quotas for allies. In 2025, he reinstated a full 25% tariff on all foreign steel and aluminum, no exceptions. An order signed Feb 10, 2025, raised the aluminum tariff from 10% to 25%, aligning with steel. These tariffs took effect on March 12, 2025, and apply worldwide. Essentially, every ton of steel or aluminum coming into the U.S. now faces a hefty tax, reversing the previous administration’s partial relaxations. The White House justifies this by citing national security and the need to boost U.S. metal industries. Indeed, the original steel tariff was credited with raising domestic production in 2018. However, such tariffs also raise input costs for American manufacturers (from carmakers to construction). Worth noting: Chinese steel’s direct share of U.S. imports is tiny (~1%), but China exports a lot of steel to third countries like Vietnam and Canada, which then export steel to the U.S. By casting a worldwide net, the U.S. aims to stop Chinese steel indirectly flooding in via other countries. Trading partners (including allies) have criticized these renewed metal tariffs – the EU, for example, calls them unjustified and had previously won a WTO ruling against the 2018 tariffs. We could see some retaliation or quota deals being re-negotiated here as well, but for now the tariffs stand, benefiting U.S. steelmakers while straining U.S. steel users.

Closing the “De Minimis” Import Loophole: In a less-publicized yet impactful policy change, the U.S. moved to end the duty-free exemption for small-value e-commerce imports. Previously, individual packages valued under $800 could enter the U.S. without tariffs or formal customs procedures (this is known as the de minimis rule). This allowed a flood of direct-to-consumer parcels from overseas (mainly China) via online retailers. In early February 2025, an executive order abruptly halted this de minimis treatment, meaning even cheap imported goods now face inspection and duty. The result was chaos at logistics centers – millions of parcels from China and Hong Kong were held up, and the USPS temporarily suspended all inbound packages from China for a day. The administration had cited the need to close a loophole exploited by companies like Shein (fast fashion) and Temu (online marketplace) that ship low-cost goods directly to U.S. consumers while avoiding import taxes. There was also a law enforcement angle: stopping the flow of illicit fentanyl and precursors often mailed from China in small packages. After an outcry, the White House partially delayed full implementation until systems are set to handle the volume. But the direction is clear – the days of tax-free $5 goodies from China showing up at your doorstep are ending. Major e-commerce players built on that model are particularly exposed: Chinese online retailers like the aforementioned Shein and Temu (popular for ultra-cheap clothing and gadgets) face a huge blow to their U.S. business. Even Amazon’s third-party marketplace (many sellers from China) is affected by tighter scrutiny and costs. For consumers, this might mean fewer ultra-cheap online deals and longer wait times for international parcels. For U.S. retail, it levels the playing field a bit against those direct-from-China sellers.

Export Controls and Tech Restrictions: While tariffs grab headlines, the U.S. has also continued policies restricting certain high-tech trade with rivals (especially China) on national security grounds. Many of these measures started under the prior administration – for instance, controls on exporting advanced semiconductors and chipmaking equipment to China (implemented in late 2022) remain in force and have even been tightened. Under Trump 2.0, we’ve seen rhetoric about further sanctioning Chinese tech companies and possibly expanding export bans. As an example, the U.S. recently investigated Chinese shipbuilding subsidies and hinted at responsive action, potentially limiting tech transfer to China’s shipbuilding and maritime sectors. There’s also talk of using tools like the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) more aggressively to cut off Chinese access to critical U.S. technology or to sanction firms that aid China’s military. On the flip side, China has its own new export controls – in mid-2025, Beijing banned exports of certain rare minerals (like gallium and germanium) vital for semiconductor production, as retaliation for U.S. tech curbs. We’ll discuss that in the next section. The takeaway: the trade war isn’t just about tariffs on goods – it’s intertwined with a tech war restricting flows of strategic technologies, which can have huge implications for industries like electronics, aerospace, and telecommunications.

This aggressive U.S. trade stance has naturally prompted strong reactions around the world. In the next section, we’ll cover how other countries have responded – from retaliation to realigning their own trade partnerships – and what broader geopolitical shifts are underway because of Trade War 2.0.

International Response and Geopolitical Shifts

The ripple effects of the renewed trade war are being felt globally. U.S. trading partners have not taken these actions sitting down; many have retaliated or adapted strategies to mitigate the impact. Let’s break down the key responses:

China’s Countermeasures and Strategy

China has responded to the U.S. tariffs with a mix of tit-for-tat tariffs, export restrictions, and strategic shifts:

Retaliatory Tariffs on U.S. Exports: Beijing rolled out its own tariff list targeting American goods the moment U.S. duties hit. Effective Feb 10, 2025 (just as the U.S. 10% China-wide tariff came online), China imposed tariffs on 80 categories of U.S. exports. This included 15% tariffs on U.S. energy products (such as coal, natural gas, and crude oil) and 10% tariffs on 72 types of U.S. manufactured goods. Notably, China aimed at American farm and industrial equipment – e.g. agricultural machinery, construction vehicles, and even commercial trucks now face a 10% Chinese tariff. By doing so, China is hitting industries concentrated in Trump-supporting regions (farm belt states, heavy machinery hubs, etc.), a calculated move to exert political pressure. These counter-tariffs remind us of 2018/19, when China targeted U.S. soybeans and aircraft. Indeed, energy and machinery have joined agriculture as China’s leverage points, since China is a big buyer of U.S. LNG and farm equipment. The immediate effect is that U.S. firms in those sectors find it harder to compete in the Chinese market as their goods become more expensive relative to European or Asian competitors.

Cutting Off Critical Mineral Exports: China has also weaponized its dominance in certain raw materials. In mid-2025, Beijing announced export controls on key minerals and metals used in high-tech manufacturing – for instance, restricting exports of rare earth elements, gallium, and germanium to the U.S. These obscure-sounding materials are actually crucial for semiconductors, electric vehicles, and defense technologies. China controls over 70% of global production of some of these inputs. A recent example: China banned exports of natural graphite, essential for EV battery anodes, which could crimp U.S. battery supply chains. By doing this, China is signaling that it can inflict pain by choking off supply of materials that U.S. tech firms and manufacturers need. It’s a reminder of 2010, when China halted rare earth shipments to Japan during a diplomatic spat. Now we see a similar tactic on the U.S. – an escalation of the “tech war” aspect of the conflict. This puts pressure on U.S. and allied countries to develop alternative sources (e.g., mines in Australia or other countries, recycling, etc.), but those solutions take time.

Blacklisting and Regulatory Pressure: China has passed new laws enabling it to blacklist foreign companies and restrict their operations in China in retaliation for U.S. actions. In 2025, there have been instances of Chinese authorities stepping up inspections, delays, or fines on American companies operating in China. A prominent example is Micron Technology, a U.S. memory chip maker: in May 2023 (pre-Trump, but part of this trend), China’s cybersecurity review effectively banned certain Micron products. That kind of pressure could intensify under Trade War 2.0, with U.S. firms in China (tech companies, consultancies, etc.) facing a tougher regulatory environment or nationalist backlash. Additionally, Chinese officials have hinted at restrictions on U.S. firms in strategic sectors – for example, considering export controls on solar panel materials or pharmaceutical precursors, where China has a strong position, if the U.S. continues to escalate.

Currency and Economic Policy: During the 2018 trade war, China allowed its currency (the yuan) to weaken past a key level, which helped offset U.S. tariffs by making Chinese exports cheaper. We may see a similar pattern now – indeed, the yuan has shown volatility. The Chinese government is also stimulating domestic demand to rely less on exports. Programs to support manufacturers (tax breaks, easier loans) and consumers (to keep spending despite any job impacts in export industries) are part of Beijing’s playbook to cushion the domestic economy. Additionally, China has doubled down on its industrial self-reliance campaign (“Made in China 2025” and beyond), investing heavily in indigenous tech and alternative markets.

Shifting Trade Partnerships: To mitigate lost U.S. sales, China is deepening trade ties elsewhere. Regional trade pacts like the RCEP (Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership), which includes China and most Asian economies (but not the U.S.), are helping Beijing redirect trade. For example, if China buys less grain from the U.S., it’s buying more from Brazil and Argentina (South-South trade is growing). Likewise, Chinese manufacturers are courting consumers in Southeast Asia, Africa, and the Middle East to reduce reliance on the U.S. market. China and Russia have also grown much closer economically (e.g., China is buying record volumes of Russian oil and gas, and in return Russia is importing more Chinese machinery and vehicles – partially replacing Western suppliers who left due to sanctions). All told, China is trying to “weather” the trade war by diversifying its import sources and export destinations. Notably, by 2023, China had already made itself less vulnerable by securing alternative suppliers for things like soybeans (Brazil) and aircraft (Airbus). This doesn’t mean the U.S. tariffs don’t hurt – they do – but China in 2025, is arguably better positioned to endure a trade war than it was in 2018.

In sum, China’s approach mixes retaliation with resilience-building. They retaliate directly to impose political costs (tariffs on U.S. exports, making Tesla or Boeing sweat in China’s market), and simultaneously accelerate plans to depend less on the U.S. (be it sourcing or sales). Geopolitically, the U.S.-China relationship has shifted from cautious cooperation to open economic rivalry. Trade War 2.0 has further pushed China to align with non-Western partners, creating a more fragmented global trading system.

Update as of March 4, 2025: Beijing retaliated with tariffs of up to 15% on a wide array of U.S. farm exports. It also expanded the number of U.S. companies subject to export controls and other restrictions by about two dozen.

Allies and Other Countries: Responses and Realignments

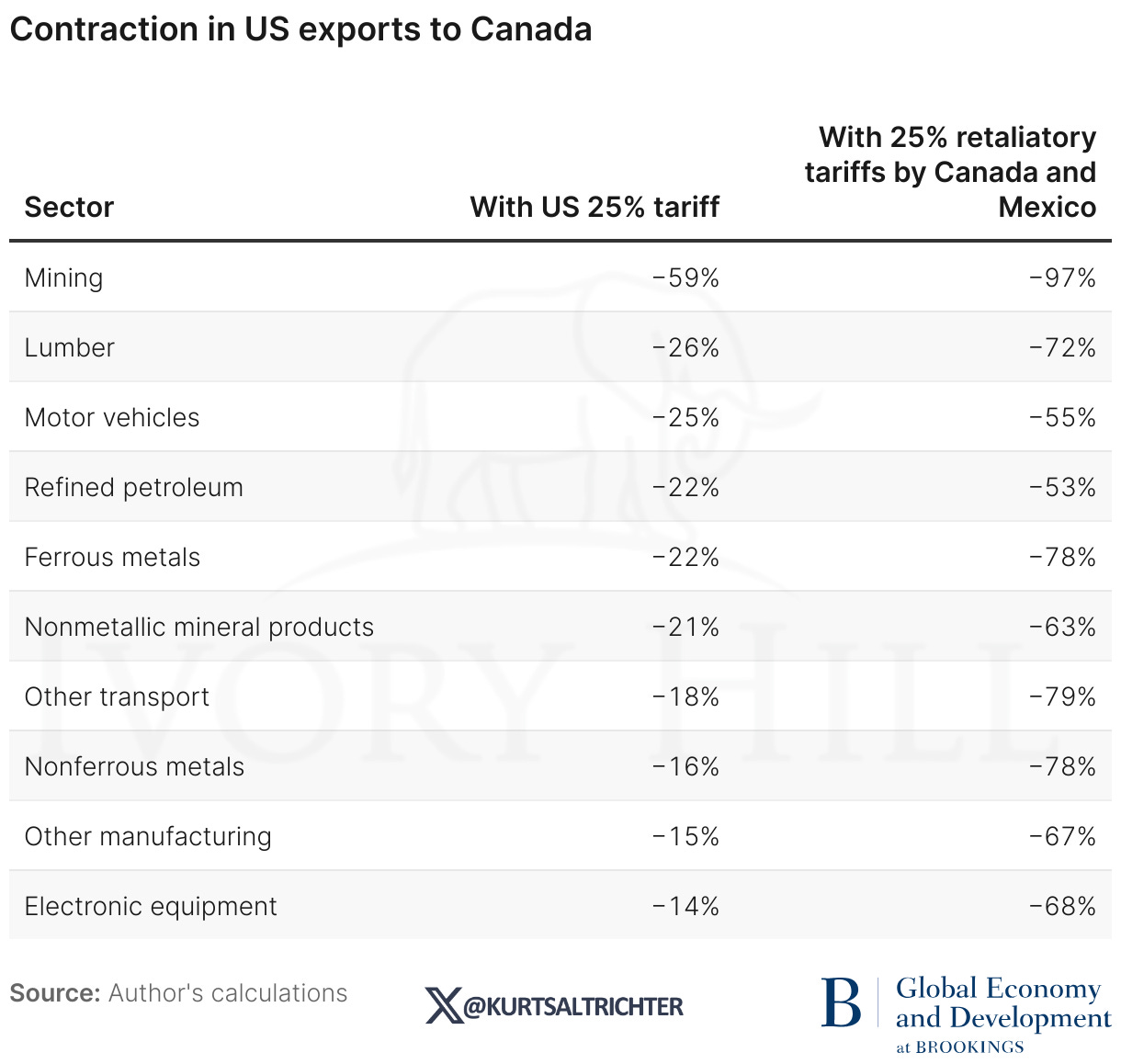

Canada & Mexico (USMCA Partners): As mentioned, Canada and Mexico narrowly avoided tariffs by negotiating last-minute deals. Canada’s response was notably firm – Prime Minister (at the time) Justin Trudeau warned of immediate retaliation, including a planned 25% tariff on $155 billion of U.S. goods if the U.S. tariffs went through. Canada had even lined up specific targets like U.S. orange juice and other consumer goods for tariffs (a strategy to exert pressure on influential U.S. industries and regions). When the U.S. paused its tariffs, Canada likewise paused its counter-tariffs. Mexico’s government, similarly, had prepared retaliatory measures (likely focusing on U.S. agriculture and industrial exports) but held off due to the truce. Both countries have since been working to address U.S. concerns (e.g., tighter border control) to avoid reigniting the tariff threat. Behind the scenes, however, they are also exploring ways to lessen their vulnerability. For instance, Canada has been seeking new markets for its products (and even pondering closer ties with Europe or the Pacific region via trade agreements), so that it’s not as beholden to U.S. trade. Mexico, benefiting from nearshoring (with many companies moving operations from China to Mexico to be closer to the U.S.), ironically, has a booming export sector – but that growth would be jeopardized if broad U.S. tariffs hit. So, Mexican officials are in a balancing act: cooperating on non-trade issues to keep Trump happy, while reassuring investors that the USMCA free trade zone remains intact. Overall, North America’s supply chains are so integrated that a trade war within NAFTA/USMCA would be mutually destructive, which is why cooler heads are likely to prevail. Nonetheless, the episode has injected uncertainty: businesses now know that even traditional allies are not 100% safe from tariffs.

Update as of March 4, 2025: Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said his country would slap tariffs on more than $100 billion of American goods over the course of 21 days. Mexico didn’t immediately detail any retaliatory measures.

European Union and UK: The EU has publicly decried the U.S. tariff escalation but is also trying to avoid a direct showdown. European officials swiftly engaged in talks with the Trump administration to seek exemptions or a compromise – especially regarding the threat of auto tariffs and the “reciprocal tariff” plan. The auto sector is a red line for the EU: Germany, for example, exports a large number of luxury cars to the U.S., and a 10% U.S. import tariff (versus 2.5% currently) would hurt German automakers. In response, the EU has hinted it could retaliate with tariffs on politically sensitive U.S. exports (just as it did in 2018 by targeting Kentucky bourbon, Wisconsin Harley-Davidsons, etc.). However, early indications are that the EU might strike a deal – possibly agreeing to reduce certain EU tariffs or regulatory barriers in exchange for the U.S. not imposing the full reciprocal tariffs. There’s precedent: in 2018, Trump and the EU reached a truce where the EU agreed to buy more U.S. soybeans and LNG, and further tariff escalation was paused. We may see something similar. Indeed, several countries (EU members, Japan, etc.) are proactively negotiating with Washington to carve out peace, recognizing that a transatlantic or transpacific trade war would compound the China conflict.

It’s also worth noting the UK, which post-Brexit is desperate for a trade deal with the U.S. The UK has signaled willingness to align with many U.S. positions (like restricting Huawei 5G gear earlier or joining the U.S. in sanctioning China’s human-rights abuses) in hopes of favorable trade terms. Under Trade War 2.0, the UK might position itself as a “friend” to be spared tariffs – for example, Britain already had a quota arrangement on steel with the U.S. that could be maintained to avoid the 25% steel tariff. The broader EU, however, has to manage internal unity – some European industries (steel, aluminum) actually benefit if the U.S. tariffs divert those exports to Europe instead, whereas car manufacturers stand to lose. So, internal EU politics are in play as they formulate a response.

Other Allies (Japan, South Korea, Australia): These countries also face collateral impacts. Japan and South Korea worry that if the U.S. goes full bore on “reciprocal” tariffs, their auto and electronics exports could be hit (both have trade surpluses with the U.S.). They have been more low-key in responses, likely seeking quiet diplomacy. Japan might revive elements of the trade talks it had with Trump in 2019 (where Japan agreed to purchase more U.S. agricultural goods to stave off auto tariffs). South Korea renegotiated the KORUS FTA in 2018 to mollify Trump; it may hope that holds. Australia, interestingly, was one of the few countries exempted from Trump’s 2018 metal tariffs (owing to close security ties). In 2025, Trump hinted at possibly giving Australia a pass again on metals. Australia is less directly targeted since it has a trade deficit with the U.S., but Canberra is carefully balancing its security alliance with the U.S. and its economic reliance on China. In fact, Australia stands to gain if China and the U.S. cut trade with each other – e.g., China might buy more Australian beef, coal, or minerals when it’s avoiding U.S. products.

Emerging Markets and Developing Countries: Many developing nations are watching this great-power clash and adjusting accordingly. Some see opportunities: for example, Vietnam, India, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia all have been courting manufacturers fleeing China’s tariffs. This trend began in the first trade war and is accelerating. Vietnam, in particular, has become a big winner; it’s now a top supplier to the U.S. of electronics, apparel, and furniture as companies re-route supply chains. U.S. multinationals like Intel, Apple, and Boeing have invested heavily in Vietnam in recent years. JPMorgan analysts project that Apple could make 1 in 4 iPhones in India by 2025 (up from almost none a few years ago) – a direct response to the need for diversification. India, for its part, is receiving more outsourcing of everything from electronics assembly to call centers, benefiting from both geopolitical alignment with the U.S. and its large labor force. “China+1” strategies (keeping some production in China but adding another country) are now mainstream for global companies to hedge against tariffs or sanctions.

However, some emerging markets also face risks. Those tightly linked to China’s supply chain can suffer if China’s exports drop. For example, South Korea and Taiwan sell a lot of electronic components to Chinese factories – if U.S. demand for China-made gadgets falls, it indirectly hits those suppliers. Similarly, commodity exporters (say, Chile for copper or Malaysia for palm oil) could feel a pinch if global growth slows due to the trade war. There’s also a concern about precedent: if the U.S. freely slaps tariffs for geopolitical reasons, other big economies might do the same, eroding the rules-based trading system. That uncertainty can deter investment in export-driven economies.

Multilateral and Geopolitical Shifts: On the world stage, these trade frictions are straining institutions. The World Trade Organization (WTO) has been sidelined – the U.S. tariffs (especially broad national-security ones) arguably violate WTO rules, and indeed the WTO ruled against the 2018 steel tariffs. But the U.S. has blocked the WTO’s appellate body, making enforcement hard. So, we’re in a power-based, rather than rules-based scenario. This has pushed countries to form more regional and bilateral trade alliances. For instance, Asian nations (ex-China) are deepening cooperation through agreements like CPTPP (Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, which the U.S. withdrew from, but others carried on) and the aforementioned RCEP. Latin American countries are also hedging: Brazil and Argentina benefit by feeding China’s commodity appetite, while Mexico tries to solidify its role as a nearshore base for U.S. companies. Africa could potentially attract more manufacturing (with incentives like the African Continental Free Trade Agreement), but that’s a slower burn.

One notable geopolitical angle: Trade War 2.0 intertwines with broader U.S.-China strategic competition. It’s not just about trade deficits, but also about technological leadership, military power (supply chains for defense), and values. The harsh trade measures have contributed to a downward spiral in U.S.-China relations, making cooperation on other global issues (climate change, public health, etc.) more difficult. Meanwhile, other major powers like the EU, Japan, India find themselves somewhat caught in the middle – aligning with the U.S. on strategic concerns about China, but also economically tied to China. This is leading to the buzzword of the year: “de-risking” (particularly used by the EU) instead of full decoupling – meaning diversify away from over-reliance on China without completely severing ties. Similarly, the U.S. is pushing “friend-shoring,” encouraging companies to produce in allied countries rather than adversaries.

In summary, the current trade war is reshaping global commerce: splitting it into blocs, motivating countries to pivot supply chains, and prompting new alliances (and fractures) based on trade interests. It’s a fluid situation – one eye is always on potential negotiations that could defuse tensions (rumors of backchannel U.S.-China talks periodically surface, though nothing concrete yet). But for now, businesses and investors must navigate a world where tariffs and geopolitical risks are the new normal. Next, let’s drill down into the specific impacts by region and sector, to see who stands to lose or gain in this environment.

Impact Analysis by Country & Region

Understanding the implications of Trade War 2.0 requires looking at how different economies are affected. Here we analyze the impacts on the United States, China, Europe, and other regions:

United States: Higher Prices, Mixed Fortunes for Industries

For the U.S. economy, the trade war is a double-edged sword. On one hand, American producers in certain protected industries benefit, but on the other hand, consumers and many businesses face higher costs. Key points on U.S. impacts:

Consumers Pay the Price: Tariffs are essentially a tax on imports, and U.S. consumers end up shouldering much of that cost in the form of higher prices. The new round of tariffs means Americans will likely see price increases on everyday goods – from groceries and household items to electronics and clothing. For example, the blanket tariffs on Chinese goods will affect a huge array of consumer products. Business Insider noted that items like medicine, cookware, staple foods, appliances, and automobiles could see cost spikes due to the tariffs. Already, grocery prices were elevated post-pandemic, and a 25% tariff on foods from Mexico or Canada would only exacerbate that (think pricier fruits, veggies, and even beer and baked goods that rely on imports). Similarly, anyone looking to buy a new car or replace a washing machine may face notably higher price tags if key components are imported. In short, inflationary pressure is a real concern – tariffs themselves directly add to inflation. The Peterson Institute warned that escalating tariffs could push U.S. inflation higher and dent GDP growth. We’re already seeing financial markets factor this in: long-term U.S. Treasury yields have risen (early in 2025) partly because investors expect higher inflation and less Fed easing given the tariff outlook.

Manufacturers and Farmers – Squeezed by Retaliation: Many U.S. industries that rely on exports are feeling the pain of foreign retaliatory tariffs. American farmers are once again in the crosshairs. China’s counter-tariffs on U.S. agricultural goods (like grains and meats) mean lost sales and potentially lower crop prices for U.S. growers, unless the government steps in with aid as it did in 2018-19. A sobering fact: even before this new flare-up, U.S. soybean farmers hadn’t regained their pre-2018 export volumes to China. Now, with China imposing new tariffs or simply shunning U.S. suppliers, farmers could see further erosion of market share. The energy sector also got entangled – China’s 15% tariff on U.S. LNG and coal makes U.S. energy less competitive in one of the world’s biggest markets. Companies in states like Texas and West Virginia (big LNG and coal exporters) could be hit. U.S. manufacturers of heavy equipment (think Caterpillar for construction machinery or Deere for farm equipment) face 10% tariffs selling into China, which could reduce their sales and profits. There’s a real possibility of job losses or lower growth in these exporting industries, and often those are good-paying blue-collar jobs. Furthermore, U.S. firms operating in China (from automakers to retail chains) could see reduced revenue if Chinese nationalism or regulations steer customers away from American brands.

Input Costs Up, Margins Down: U.S. businesses that rely on imported parts or materials are now paying more for those inputs. For instance, an American electronics company importing circuit boards from China now pays 10% more due to the tariff. A car manufacturer sourcing certain components from Mexico might face the risk of a 25% surge in cost if tariffs snap back. These companies must either absorb the cost (hurting their profit margins) or pass it on to consumers (which, as noted, hurts demand). Many small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which lack the pricing power of giants, will feel the squeeze. A concrete example: U.S. auto parts makers use specialty metals – with a 25% tariff on imported steel/aluminum, their raw material bills have jumped, making it harder to compete or forcing up the price of the final car. The Tax Foundation estimated that the full range of threatened tariffs (including on Canada/Mexico) could amount to a $106 billion tax increase for Americans in 2025, which is money out of consumers’ and companies’ pockets.

Beneficiaries – Steel, Aluminum, and Possibly Some Onshoring: On the flip side, U.S. steel and aluminum producers are clear winners of the trade war, at least in the short term. With foreign metals now more expensive, domestic mills can charge higher prices and increase market share. Indeed, U.S. steelmakers cheered the renewed 25% tariff – in 2018, they saw a boost in utilization and profits when the tariff first came in. We might also see a modest bump for industries like textiles, furniture, or apparel manufacturing in the U.S. if companies decide to bring some production back to avoid tariffs. The administration is certainly hoping for a renaissance in “Made in America” manufacturing. There are anecdotal reports of factories expanding in certain sectors (for example, some electronics assembly moving to the U.S. or Mexico from China to bypass costs). However, it’s important to keep perspective: the first trade war didn’t spark a massive U.S. manufacturing revival – factory employment stayed roughly flat even in a booming economy. High tariffs alone may not overcome the cost advantages of producing in Asia or elsewhere. But certain niche industries or strategically funded projects (like semiconductor fabs spurred by the CHIPS Act) will grow, aided by both protection and subsidies.

Regional Variances – Different States, Different Effects: The impact of Trade War 2.0 is uneven across the U.S. Industrial Midwest states (Ohio and Michigan), which might see a boost for steel mills and some heavy industry, but their automakers could suffer from higher input costs and potential retaliatory moves (e.g., if Europe taxed Harley-Davidson again, Wisconsin would feel it). Farm belts and energy-producing states (Iowa, Texas, North Dakota) are hurt by lost foreign markets for crops and LNG/oil. Coastal states that are import-reliant (California and New York) will see consumer prices rise, potentially dampening retail activity. A Brookings analysis highlighted that many of the counties most exposed to China’s retaliatory tariffs are rural, export-heavy counties – often places that voted for Trump, ironically. These local economies could face job losses if factories cut shifts due to decreased export orders. The federal government might resort to mitigation measures like financial aid to farmers or affected businesses (like the farm aid packages in 2018-2019) to cushion the blow.

Macro and Market Impact: In aggregate, if all the threatened tariffs materialize, U.S. GDP growth could be shaved by some amount (various estimates range from a few tenths to over a percentage point off growth, depending on escalation). Inflation could run higher – Barclays estimated that the proposed tariffs and retaliation could drag S&P 500 corporate earnings down by ~2.8% and would particularly hurt the tech and manufacturing sectors. Investors have noticed: trade-sensitive stocks (like certain automakers, chip companies, retail giants) have seen higher volatility due to trade headlines. We’re not citing specific index moves here, but the market has been jittery with each new tariff announcement, as traders try to gauge which sectors will be hardest hit. The Federal Reserve is in a tough spot too – trade-driven inflation is a supply-side issue, which interest rate hikes alone can’t fix easily, yet the Fed might be forced to keep rates higher for longer to quell broad inflation. So, the trade war is even influencing monetary policy expectations.

In summary, for the U.S.: consumers and many businesses lose more than they gain from a broad tariff war, at least in the near term. Certain domestic industries are protected and might add jobs, but those gains are likely smaller than the losses in export industries and the cost burden on everyone else. As financial advisors, we keep an eye on how this might affect various investments – for example, U.S. companies with heavy import costs or China exposure may face headwinds, whereas some domestic-focused materials or defense companies might be more insulated or even advantaged. The key is diversification and quality, to weather these policy-induced shocks (more on that later).

China: Economic Headwinds and Accelerated Self-Reliance

China’s economy, the world’s second largest, is feeling the strain from Trade War 2.0, though it’s showing resilience in some areas. Let’s outline the impact on China:

Export Slowdown and Manufacturing Hit: The U.S. tariffs (and potentially reduced orders) are a direct hit to China’s export sector. The U.S. is one of China’s top export markets; with new tariffs, Chinese goods become more expensive for American buyers, likely reducing demand. Chinese exports to the U.S. had already dipped during the first trade war (China’s trade surplus with the U.S. fell after 2018). Now, with all Chinese exports to the U.S. taxed at 10% or more, it’s logical we could see a further decline in those shipments. Industries in China that heavily ship to the U.S. – electronics, appliances, furniture, toys, textiles – will see pressure. Some factories may face layoffs or closures if orders divert to Southeast Asia or back to America. The Pearl River Delta and Yangtze River Delta regions (China’s manufacturing heartlands) could see rising unemployment in export-oriented towns. This comes at a time when China’s overall economic growth has been moderating (even aside from trade war factors), so the tariffs are an unwelcome headwind.

Supply Chain Realignments – Loss of Some Foreign Investment: Over the past few years, and now accelerated in 2025, many multinational companies have been rethinking their “China strategy.” The trend of shifting some production out of China (“China+1”) means China may not see as much future foreign investment in manufacturing. For instance, companies like Apple have moved parts of their supply chain to India and Vietnam; garment makers shifted some orders to Bangladesh or Vietnam; electronics firms set up assembly in Mexico. This doesn’t cause an immediate collapse – China still has an unparalleled ecosystem for manufacturing – but gradually, China’s share of global manufacturing exports could erode. Data already showed China’s share of Apple’s supplier locations fell from nearly 47% to 36% in recent years. If tariffs persist, more firms will decide it’s worth investing outside China to avoid uncertainty. This means potentially fewer factory expansions in China and more in other Asian nations, impacting China’s industrial growth.

GDP and Growth Impact: Economists estimate the trade war could shave some percentage points off China’s GDP growth in the coming year or two. China’s growth was around 6% in 2019 and had slowed below that even pre-COVID; with trade tensions, it might struggle to hit those levels. However, China is deploying measures to prop up growth: interest rate cuts by the PBoC, infrastructure stimulus to create domestic demand, and incentives for consumers to spend (like subsidies for electric cars and appliances). These may offset some of the drag from weaker exports. Still, there’s no doubt that net exports will contribute less to China’s growth, and that some industries (especially those with thin margins that can’t absorb tariffs) will contract. We also must consider investor confidence: U.S. and other Western companies might delay or cancel expansion plans in China given the uncertain trade climate, which can subtly weigh on growth and productivity.

Chinese Consumer Impact: While the Chinese government can manage a lot, one area of concern is consumer and business sentiment in China. The first trade war in 2019 saw a dip in Chinese consumer confidence, and there were nationalist boycotts of certain U.S. brands (remember the mini boycotts of Apple or U.S. automakers at times). If the populace perceives the U.S. as attacking China’s economy, they might rally around domestic brands – which could hurt U.S. companies like Apple, Nike, GM, Starbucks, etc., that rely on Chinese customers. Indeed, some reports in 2025 indicated Chinese government agencies restricting the use of Apple iPhones, possibly as a tit-for-tat for U.S.-tech restrictions. The longer the standoff continues, the more Chinese consumers may pivot to homegrown products (which the government would welcome as part of its self-reliance push).

Acceleration of Self-Reliance (Tech and Beyond): A perhaps unintended consequence (from the U.S. perspective) is that the trade war is turbocharging China’s efforts to become economically self-reliant. China’s leadership has explicitly talked about “dual circulation” – boosting domestic consumption and indigenous innovation so that external dependency is reduced. In technology, for example, U.S. export controls on semiconductors have spurred China to pour billions into its own chip industry. While China is still behind in cutting-edge chips, they are rapidly improving (some Chinese firms recently unveiled a 7nm chip made without EUV lithography – a sign of progress under sanctions). The trade war gives political cover for massive state investment in everything from chip fabrication, AI, renewable energy tech, aerospace (COMAC jets to rival Boeing/Airbus), to agriculture (so it can feed itself better and rely less on U.S. grains). In the short run, this is costly and inefficient (China will reinvent some wheels rather than buying the best global tech). But in the long run, it could make China a more formidable competitor in high-tech industries. Already, China’s EV sector is a good case study: faced with foreign competition and supported by subsidies, Chinese EV makers like BYD, Nio, and Xpeng have innovated fast – now they dominate their home market and are expanding abroad, even as U.S. automakers’ share in China shrinks. Similarly, China has basically eliminated its need for U.S. commercial aircraft for now by developing the C919 passenger jet (and by leaning on Airbus). These steps might help insulate China from trade pressure over time, but in 2025 they’re still in progress, meaning some short-term pain for long-term gain.

Financial Markets and Yuan: China’s stock markets and the yuan currency have been sensitive to trade news. The yuan has weakened at times beyond the psychologically important 7.3 per dollar level in 2025 as tariffs kicked in, which actually helps Chinese exporters by offsetting some tariff cost (a cheaper yuan makes Chinese goods cheaper in dollar terms). But authorities manage the currency carefully to avoid capital flight or too much inflation. The central bank has tools to stabilize the yuan if needed. Chinese equities, especially export-oriented firms (e.g., manufacturing companies, shipping firms), saw declines when the trade war escalated. Conversely, companies catering to domestic demand or aligned with government substitution initiatives (like local chipmakers or EV battery producers) have gained favor among investors. The government might also restrict outbound investment or encourage domestic capital to stay home to ensure funding for its industries during this standoff.

In essence, China is enduring a storm – battered but not broken. The trade war has imposed costs (lost export revenue, higher import costs for certain tech components, lower growth for some firms). But China’s large internal market and decisive policy response provide some cushion. We’re likely to see China continue to retaliate in measured ways (to avoid full rupture), while simultaneously reducing vulnerabilities (developing alternate trading partners and technologies). For investors, China’s markets and companies with high China exposure are volatile right now. But we also see secular trends where China is pushing ahead (like clean energy, EVs, AI) that could create opportunities in the longer run, albeit with a strong domestic bias. The immediate outlook is one of caution – slower growth and plenty of geopolitical risk – but not a collapse.

Europe: Caught in the Middle, Bracing for Impact

Europe finds itself in a delicate position in this U.S.-led trade war. The EU isn’t the primary target like China is, but it’s indirectly affected and at times directly threatened by U.S. tariffs (e.g., autos, metals).

Threat to Key Industries (Autos in Particular): Europe’s economic engine, Germany, relies heavily on manufacturing exports – notably cars and machinery. The potential U.S. auto tariff of 10% (up from 2.5%) is a significant threat for German automakers like Volkswagen, BMW, and Daimler (Mercedes-Benz). These companies export hundreds of thousands of vehicles per year from European factories to the U.S. A quadrupling of the import tax would either force them to raise U.S. prices (hurting sales) or cut profit margins drastically. The European auto sector is already navigating other challenges (EV transition, competition from Tesla and new Chinese EVs); a tariff hit could mean lower production and possibly job cuts in Europe. In fact, European carmakers might accelerate the shift of some production to their U.S. plants (many have factories in the U.S. South) to avoid tariffs – a minor win for U.S. manufacturing but a loss for European plants. Beyond autos, Europe’s aerospace giant Airbus benefited from China’s pivot away from Boeing, but if U.S.-Europe trade relations sour, the U.S. could retaliate in the long-running Boeing-Airbus subsidy dispute (that tit-for-tat had led to U.S. tariffs on European wines and planes, and EU tariffs on U.S. goods until a truce in 2021). Renewed tension could see those tariffs come back into play.

Economic Growth and Sentiment: The EU economy is already dealing with energy cost issues and a post-COVID slowdown. A trade war on multiple fronts adds another drag. If global trade volumes decline, export-oriented economies like Germany and Italy suffer. The uncertainty also hits business confidence – European firms might delay capital spending due to unclear trade rules. The European Central Bank has mentioned trade disputes as a downside risk to the outlook. Some analysts estimate a full-blown tariff war (U.S. vs EU in addition to U.S. vs China) could knock a percent or so off EU GDP growth. Key exporters like Germany could flirt with recession if their exports drop significantly. Meanwhile, consumers in Europe could face higher prices on some goods too, especially if they retaliate with tariffs (for instance, EU’s past retaliation on U.S. goods raised prices of American bourbon, jeans, etc. in Europe). However, Europe might selectively benefit, if say, Chinese tariffs on U.S. goods cause China to buy from Europe instead. For example, if China stops buying U.S. agricultural machinery, European makers like Siemens or CNH Industrial might pick up some sales.

EU’s Balancing Act – “De-Risking” from China, Managing U.S. Relations: Europe has its own concerns about China (e.g., dependency on Chinese components, and a huge trade deficit with China). The European Commission has advocated “de-risking,” not decoupling – meaning reducing reliance on China in critical areas like semiconductors, batteries, and critical minerals. The U.S. trade war kind of nudges Europe in that direction too. We’ve seen the EU implement new tools: a mechanism to screen and potentially block outbound investments in sensitive tech to adversaries, a ban on certain telecom gear from Huawei, and an investigation into Chinese EV subsidies (which could lead to EU tariffs on Chinese electric cars to protect European automakers). So, in an interesting twist, Europe is softly aligning with the U.S. goal of checking China’s trade power, but it prefers a more multilateral, less combative approach. At the same time, Europe values its trade relationship with the U.S. – the two economies are deeply intertwined. Thus, Europe is likely to negotiate and perhaps grant the U.S. some wins (like opening its market a bit more to U.S. goods or cooperating on WTO reform) to avoid being lumped into Trump’s tariff crosshairs. The UK, outside the EU now, might even more readily make concessions to avoid any friction.

Retaliation Preparedness: The EU has historically been a savvy and precise retaliator when provoked. In 2018, they targeted iconic American exports from politically important states (Harley-Davidson bikes, Levi’s jeans, bourbon whiskey) to maximize political pain for U.S. leaders. If Trump were to ignore negotiations and impose tariffs on European goods (like cars, cheese or wine), the EU almost certainly has a list ready to respond in kind. This tit-for-tat could escalate, but given both sides are advanced economies, there’s also incentive to settle (as they did with the Airbus/Boeing subsidy dispute with a truce in 2021). One should note: European retaliation could impact specific U.S. companies significantly – e.g., American Whiskey distillers lost some EU market share when hit with tariffs, though they recovered once tariffs were lifted. So, companies like Levi’s, Harley, or even tech companies (the EU could consider digital services taxes or other means) keep a close eye on U.S.-EU trade diplomacy.

Peripheral Europe and UK: Countries on Europe’s periphery (Eastern Europe, for instance) often supply parts to German factories, so a decline in German exports can hurt their economies too (through supply chain linkages). The UK, having left the EU, might try to capitalize by positioning as a low-tariff route to the U.S., but that’s limited by rules of origin (and the UK doesn’t have a free trade deal with the U.S. yet). If anything, the UK might suffer if its car exports to the U.S. face tariffs, and it doesn’t have the collective weight of the EU to negotiate exemptions. However, the UK’s economy is more services-heavy, and services aren’t directly affected by tariffs (though a souring global relationship can spill into services too).

In summary, Europe is somewhat of a bystander trying not to get hit by stray bullets. A transatlantic trade war is not in Europe’s interest, so we expect intense diplomacy to prevent one. But Europe will also not hesitate to defend its interests if needed. For investors, European equities could be hampered by these uncertainties, especially in export sectors. Conversely, if the U.S. and EU reach some accommodations, that could remove a cloud and benefit European markets. European companies that are diversified (both in market and production) will be more resilient, whereas those solely reliant on exports of a few products might be more vulnerable now.

Asia (Ex-China): Winners, Losers, and New Dynamics

The rest of Asia, excluding China, sees a mix of opportunities and challenges from Trade War 2.0:

Southeast Asia and India – Supply Chain Winners: As mentioned earlier, countries like Vietnam, Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia, and India have been beneficiaries of companies shifting production out of China. This trend is likely to continue and even accelerate as tariffs persist. Vietnam in particular stands out – it has become a major exporter of electronics and apparel to the U.S. and Europe, effectively picking up the slack from China in certain categories. In fact, Vietnam’s exports to the U.S. jumped so much after the first trade war that the Trump administration (in 2020) labeled Vietnam a currency manipulator and threatened tariffs, calling it “almost the single worst abuser of everybody” at one point. However, no broad tariffs were imposed on Vietnam, and in the current scenario, the U.S. seems more focused on China/Mexico/Canada. Vietnam’s integration into global supply chains (Samsung produces a huge share of its smartphones there, for example) means it is most exposed in Asia to knock-on effects. One nuance: Vietnam also imports lots of intermediate goods from China (like electronics components, steel) to produce its exports. So, if Chinese supply is restricted or costlier, Vietnam can be indirectly affected. But overall, ASEAN countries are enjoying increased foreign investment as companies adopt a “China+1” model. India too is seeing momentum – global giants (Apple, Foxconn, Samsung, etc.) are investing in Indian factories, and India’s government is keen to capture this opportunity with incentive programs. If the U.S. diversifies procurement (say, buys more pharmaceuticals or textiles from India instead of China), India gains. However, India must manage quality and scale issues; it’s making strides, like getting a chunk of iPhone assembly. Bottom line: parts of Asia are effectively a “trading hubs shift” – the production of goods consumed in the West is moving from China to various other Asian locales. That’s positive for those economies (jobs, exports, investment), though they also have to be careful not to become targets themselves.

East Asia – Caught in Supply Chain Crossfire: South Korea, Taiwan, and Japan are advanced economies heavily tied into regional supply chains. They export high-tech components and machinery to China (and elsewhere). If Chinese export production slows, demand for intermediate inputs from these countries could dip. For instance, South Korea sells semiconductors and chemicals that end up in Chinese-made electronics – less Chinese output means less Korean intermediate exports. Taiwan’s massive electronics sector (like TSMC making chips) could see shifts; however, with the U.S. restricting chip exports to China, some Taiwanese firms might benefit from Chinese companies having to turn to alternative suppliers (though in cutting-edge chips, no one can supply what the U.S. has banned). Japan provides specialized equipment (for semiconductor fabrication, auto parts, etc.) – some of that could face Chinese import restrictions if China retaliates in kind. However, Japan has also been working closely with the U.S. on tech restrictions, and it stands to gain if Western companies prefer to source from Japan instead of China for things like EV batteries or electronics. South Korea and Japan also benefit from less competition from Chinese goods in the U.S.: e.g., if Chinese electronics are pricier due to tariffs, Korean and Japanese brands might capture more U.S. market share in TVs, appliances, etc. But again, the integrated nature of supply chains muddles this – many “Korean” or “Japanese” products still have components made in China.

Commodity Exporters and Others: Countries like Australia (minerals, energy) and Indonesia (commodities) might see mixed effects. If China buys less from the U.S., it might buy more from them. Indeed, with tariffs on U.S. energy, China could up purchases from Indonesia or Qatar for LNG, for example. Australia could sell more coal or gas to China to replace U.S. supply (although Australia-China relations have their own tensions). Oil prices globally can be influenced by trade war sentiment due to growth outlook changes, affecting Middle Eastern economies too. But since energy was explicitly tariff-targeted, some shifting of trade flows will happen (e.g., China taking more Middle East oil, the U.S. maybe sending more oil to Europe instead).

ASEAN as a Bloc: Interestingly, ASEAN overtook the EU as China’s largest trading partner recently. If U.S.-China trade shrinks, China-ASEAN trade will become even more important. A lot of investment will flow within Asia – e.g., Chinese companies setting up in Vietnam to circumvent tariffs by doing final assembly there (there were cases of Chinese goods being transshipped through Vietnam to dodge U.S. tariffs, which U.S. Customs cracked down on). So, ASEAN has to be careful not to be seen as a “back door” for Chinese exports or they could face anti-circumvention duties. But legitimately, ASEAN could become a more self-contained production zone with RCEP reducing tariffs among members. That could boost intra-Asian trade independent of the West.

WTO and Trade Architecture: Asian countries, like others, are concerned about the erosion of the multilateral trading system. Many have benefited from the predictable rules of the WTO. They see the U.S.-China clash as something that could permanently alter how trade is conducted – possibly to their detriment if it becomes more power-based. Some are advocating for reforms or at least ensuring that regional agreements (like CPTPP, which Vietnam, Malaysia, Singapore and others are in, and which Japan leads now) step into the void. Notably, China has applied to join CPTPP (though that’s a long shot politically), and the UK joined this year. The U.S. is absent, which means Asia is charting its own course. We also have the new Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) initiated by the U.S. under Biden (bringing together many Asian countries on standards and supply chain cooperation), but it’s not a traditional trade deal (no tariff cuts). If Trump continues a hard unilateral approach, Asian countries might double down on intra-Asia partnerships and trade with Europe to hedge against U.S. unpredictability.

In summary for Asia ex-China: Southeast Asia and India are the relative “winners” – attracting investment and export growth as global supply chains adjust. Northeast Asia (Korea, Japan, Taiwan) navigates complex impacts – some positive (less competition from China, friendlier U.S. ties) and some negative (loss of China demand). Everyone in Asia is adapting to a world where the U.S. and China are less entwined – building regional resilience, courting foreign investors diversifying from China and balancing relations carefully. For investors, this means looking at emerging markets in Asia not as one monolith but individually: e.g., Vietnam’s manufacturing boom vs. Korea’s possibly softer export growth and India’s rise but with execution risks, etc. Country selection and understanding supply chain linkages become key.

Other Regions (Latin America, Africa): Shifts on the Sidelines

Finally, a quick note on other regions:

Latin America: Countries like Brazil and Argentina gained in the first U.S.-China trade war when China started buying their soybeans and meats over U.S. supplies. They stand to continue benefiting from China’s agricultural diversification. Brazil has become the top soybean supplier to China, and that looks permanent. If China puts high tariffs or bans on U.S. corn or pork, Latin American exporters (Argentina for soy/corn, Brazil/U.S./Canada for pork – Canada might gain too if it’s not tariffed by China) will fill the gap. Mexico, we’ve discussed as part of North America – it is vulnerable if the U.S. revisits the tariff threat, but ironically also benefiting from nearshoring as U.S. companies shift from China to Mexico for production. On the manufacturing side, Mexico and Brazil could see opportunities – for instance, if U.S. firms avoid China for pharmaceuticals or chemicals, they might invest more in facilities in those countries. But Latin America also has internal issues (political instability and infrastructure gaps) that can limit how much they capitalize. One interesting dynamic: if Chinese goods face tariffs in the U.S., Chinese firms might consider producing in Latin America to serve the U.S. market tariff-free (especially in Mexico due to USMCA). We’ve seen some Chinese auto companies building cars in Mexico, etc. So, Latin America could become a production base for Chinese capital to access U.S. without tariffs, effectively altering investment flows.

Africa: African nations are more peripheral in this trade war but not unaffected. The U.S. has a trade program (AGOA) that gives some African exports tariff preferences, which could become relatively more attractive if Chinese goods are pricier. For example, apparel from Ethiopia or Kenya might compete better in the U.S. vs. Chinese apparel with tariffs. However, Africa’s capacity is still limited and AGOA’s future uncertain (it expires in 2025 unless renewed). China is a huge investor in Africa; if China’s economy slows, its commodity appetite (for oil, copper, cobalt, etc.) might soften, which could hurt African commodity exporters (e.g., Angola for oil, DRC for cobalt). Conversely, China might double down on Belt and Road projects in Africa to secure alternative trading partners, which could bring more infrastructure investment to Africa. We might also see more localization of production – for instance, Chinese companies set up factories in Africa (like textiles in Ethiopia, or tech assembly in Egypt) as part of a longer-term strategy to diversify manufacturing.

Middle East: The Middle East is mainly impacted via oil and global growth. If the trade war dents global growth, oil demand could drop, affecting Gulf economies. However, oil has so many variables (like OPEC decisions, Russia-Ukraine war impact) that the trade war is just one factor. On the flip side, China’s reduced energy imports from the U.S. means they’ll rely more on Middle Eastern suppliers – which those countries welcome. Also, Gulf states are strengthening ties with China (witness Saudi Arabia’s growing partnership with Beijing), partly because China is a huge customer for crude. The U.S. is also less directly involved in Middle East energy than before (due to shale boom making U.S. more self-sufficient), so the Middle East may lean eastward economically.

Now that we’ve surveyed the global impact, let’s zero in on how different sectors and industries are faring in this trade war environment, and identify which ones are most positively or negatively affected.

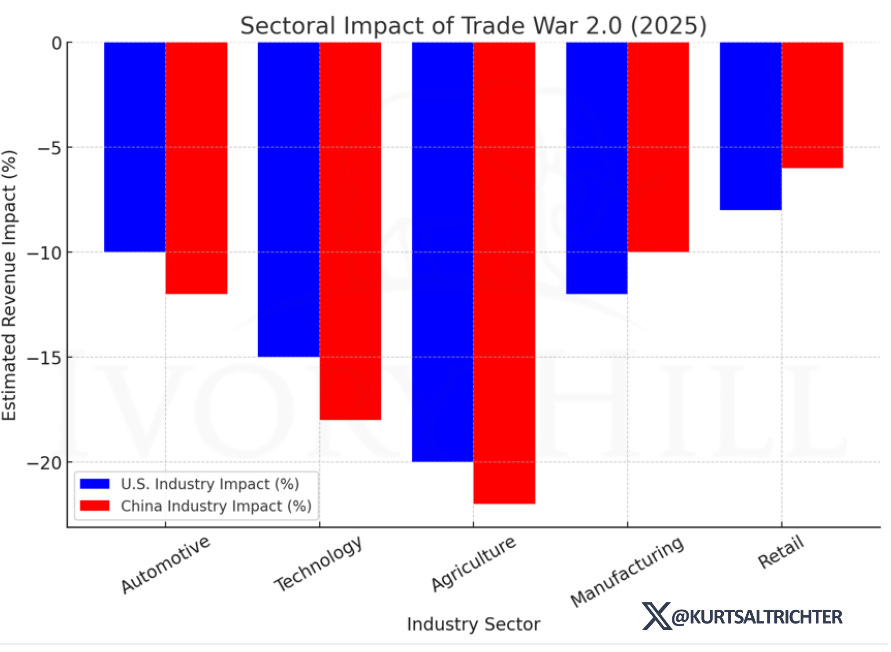

Sector Impacts: Industries in the Crossfire

Certain sectors are feeling the brunt of Trade War 2.0 (or in some cases, finding silver linings). We’ll examine a few key sectors: manufacturing & materials, technology, automotive, agriculture, consumer/retail, and others, highlighting which industries are hurt or helped and a few notable companies in each.

Manufacturing & Materials

Metals & Mining: The clearest winners of U.S. trade policy are domestic steel and aluminum producers. With a blanket 25% tariff on foreign steel/aluminum, U.S. producers like Nucor, U.S. Steel, and Alcoa have a protected home market. They can sell more and potentially at higher prices (indeed, U.S. steel prices spiked after the 2018 tariffs). Steel industry employment ticked up post-2018, and we could see a similar boost now. These companies also benefit from the infrastructure spending going on (though higher interest rates might offset some construction demand). On the flip side, steel and aluminum users – construction firms, packaging companies (cans), machinery makers – face higher input costs and have lobbied against the tariffs. Some smaller foundries or metal fabricators that rely on specialty imported metals might be squeezed. In mining, if China restricts exports of rare earths, it benefits non-Chinese producers. For instance, Lynas Rare Earths in Australia or MP Materials in the U.S. could see more demand as Western companies seek non-Chinese sources for critical minerals. The U.S. government is also likely to support domestic mining of lithium, nickel, etc., creating opportunities (though environmental permitting remains a hurdle).

Industrial Machinery & Equipment: This sector is mixed. U.S. manufacturers of industrial equipment for export (like Caterpillar, Deere, farm and construction gear) face retaliatory tariffs (China’s 10% on ag machinery, etc.), which can hurt sales. For example, Deere’s tractor exports to China become pricier against European or Japanese competitors. Caterpillar noted back in 2019 that tariffs and slower China demand were headwinds; that theme returns now. However, companies that primarily serve the domestic U.S. market might see some benefit if their foreign competitors’ products are tariffed. Also, the hope is that tariffs may induce some foreign manufacturers to locate production in the U.S. to avoid the tariffs – which could increase demand for factory automation equipment domestically. Construction materials (like cement, lumber) aren’t directly tariff-impacted as much, but any slowdown in construction (if economy wobbles due to trade war) could soften those markets.

Aerospace & Defense: Aerospace is sensitive. Boeing, as discussed, lost market share in China to Airbus. China’s state airlines have not placed significant new Boeing orders for years, and with geopolitical tensions high, that trend could continue – beneficial to Airbus and perhaps to China’s nascent COMAC. If U.S.-EU trade relations worsen, Boeing-Airbus disputes could flare. Defense contractors are less directly impacted by trade war (their customer is mainly the U.S. government), and in fact, heightened geopolitical tensions can boost defense spending. However, some defense firms rely on rare earths or electronics from China; supply chain decoupling in defense has become a strategic priority (e.g., finding non-Chinese sources for jet engine magnets, etc.). The U.S. trade policy might encourage onshoring of those supply chains.

Chemicals & Plastics: The chemical industry is globally integrated. In the first trade war, China put tariffs on U.S. chemicals and plastics, and the U.S. taxed some Chinese chemicals. The new round likely continues that. Some U.S. chemical companies have large investments in China (like Dow, DuPont) which could be at risk if operations there are restricted. Also, the U.S. exports a lot of propane and other feedstocks to China, which China may tariff or source from elsewhere. Conversely, companies that make chemicals in other countries might take share. This sector’s impact is a bit nuanced and often these firms can adapt by rerouting products through global subsidiaries.

Energy (Oil & Gas): Energy deserves mention too. The U.S. has become a major exporter of LNG (liquefied natural gas) and crude oil. China’s 15% tariff on U.S. LNG makes U.S. gas less competitive in China, so Chinese buyers will favor Qatar, Australia, or Russia LNG. U.S. LNG developers might find it harder to sign long-term contracts with Chinese utilities now. Similarly, a 10% tariff on U.S. crude discourages Chinese imports of it, so China will buy more Middle Eastern or Russian crude (which incidentally can be cheaper due to sanctions on Russia). This could slightly widen the price spread for U.S. oil (maybe Gulf Coast crude trades a bit cheaper since one big buyer is less accessible). However, energy is a global market; if China doesn’t buy U.S. oil, someone else likely will, so the effect might be muted beyond specific trade flows. U.S. energy companies might redirect exports to Europe or other Asian markets. One thing to note: if Canada had faced a 10% oil tariff (which was suggested at one point), that would raise costs for U.S. refineries reliant on Canadian heavy crude, potentially increasing U.S. gasoline prices. Fortunately, that 10% on Canadian oil was averted for now.

Technology & Electronics

This sector is at the heart of the U.S.-China economic rivalry, and it’s experiencing significant disruption:

Semiconductors: Perhaps the most strategically significant sector. The U.S. has restricted exports of cutting-edge chips to China, and China responded with measures like banning exports of certain chipmaking minerals and investigating U.S. chip firms in China. U.S. chip companies like Qualcomm, Intel, Nvidia and Micron have large portions of their revenue coming from Chinese customers (either directly or via sales to companies that sell in China). For instance, Qualcomm historically derived well over half its revenue from China (through smartphone chip and licensing sales to Chinese phone makers) – this heavy exposure is a vulnerability. As China pushes domestic alternatives (like using Huawei’s Kirin chips or other local suppliers), companies like Qualcomm could see market share erode. Micron was specifically targeted by China (banned from selling to Chinese critical infrastructure), which hurts its sales in China (a major memory market). Nvidia and AMD have lost the ability to sell their top AI chips to China due to U.S. export controls, which cuts off a huge market (Chinese tech firms were big buyers for data centers). These firms have scrambled to offer slightly neutered versions of their chips that comply with rules, but the advantage might shift to Chinese chip designers (like Huawei’s recent claims of a 7nm chip) in the Chinese market. On the other hand, semiconductor equipment makers in the U.S. (Applied Materials, Lam Research) and their Japanese and Dutch counterparts are restricted from China sales – that’s a loss for them, but potentially a gain for any nascent local Chinese tool makers. Taiwan’s TSMC is in a delicate spot: it cannot sell advanced chips to Chinese companies like HiSilicon (Huawei’s chip arm) due to U.S. rules, yet China is its neighbor and a big market for other chips; it’s following U.S. law but that means forgoing some business. Meanwhile, TSMC is investing in the U.S. (Arizona fab) due to U.S. pressure. The global semiconductor supply chain is being forced to rewire – with more geographic separation between U.S.-aligned chip production and China’s chip ecosystem. In the long term, this may lead to redundant capacity (less efficiency) and higher costs for the industry. In the short term, companies are adjusting by relocating some high-tech production to friendlier shores (TSMC and Samsung building in USA, etc.) and segmenting product lines for China vs. rest-of-world.

Consumer Electronics: This covers phones, computers, TVs, appliances – many of which are primarily made in China or include Chinese-made components. Tariffs on these products mean higher costs. Notably, the 2018-2019 tariffs spared many consumer electronics like smartphones and game consoles to avoid angering U.S. consumers, but the new stance of “tariff everything” means even devices like iPhones, laptops, and PlayStations could carry a tariff now. That is a huge deal: Americans love their gadgets, and a 10-25% price jump is noticeable. Companies like Apple, Dell, HP, Microsoft (Surface tablets), Sony (PlayStation), Nintendo, etc., which produce hardware in China, will have to decide whether to absorb the cost, raise prices, or shift production. Many have been quietly moving some assembly to places like India, Vietnam or Taiwan. Apple, for example, started making some AirPods in Vietnam and a small share of iPhones in India. But China still accounts for ~70-75% of Apple’s manufacturing footprint. It’s not trivial to move out overnight – China’s supply chain is very efficient. So, in the near term, companies might accept lower margins or tweak their supply chain (ship to another country for final assembly to claim different origin – though rules are tight on that). U.S. consumers might see the next iPhone model cost more or maybe new discounts aren’t as generous. Alternatively, retailers might try to eat some cost to keep prices stable. This dynamic will vary by product and company. Electronics retailers (Best Buy, etc.) could see sales volumes affected if prices jump significantly.

Telecom & Networking: The U.S. continues to ban or restrict Chinese telecom gear (Huawei, ZTE) from its networks and allies. Conversely, China could retaliate by limiting or scrutinizing U.S.-made networking products or services. Cisco, a big U.S. networking company, has found it tough to sell to China for years due to distrust, and that remains. Also, any U.S. software or cloud services might face more Chinese firewalls or bans (e.g., Microsoft and IBM enterprise services). On consumer side, apps like TikTok (Chinese-owned) face potential banning or forced sale in the U.S. for security reasons – that’s separate from tariffs but part of the tech decoupling.

Internet & E-Commerce: Not directly tariffed since it’s services, but U.S. internet giants (Google, Facebook, Amazon) are largely blocked from China’s market for other reasons. Chinese e-commerce players like Alibaba or Shein, which are trying to operate in the U.S., face new obstacles (like the de minimis rule change hitting Shein/Temu). Amazon relies on many Chinese third-party sellers for products – if those sellers find it harder to send goods to the U.S. or face tariffs, Amazon’s marketplace could see fewer cheap offerings, possibly benefiting domestic sellers or sellers from other countries.

Software and IP: One possible positive: U.S. companies in software or services that don’t rely on physical supply chains are relatively insulated from tariffs. In fact, they might benefit if hardware gets more expensive – perhaps consumers spend more on digital goods? But if the global economy slows, enterprise software spending could soften too. Also, the trade war has rekindled concerns about IP theft and forced tech transfer in China – the Phase One deal had IP protections, but with that essentially sidelined, U.S. tech firms might be more cautious about R&D in China.

Automotive

The auto industry is front-and-center in multiple trade war fronts: U.S.-China and U.S.-North America, and even U.S.-EU.

U.S. Automakers (GM, Ford, Stellantis): They face a multi-faceted challenge. If the U.S. slaps tariffs on autos/parts from Mexico and Canada, the Detroit Big Three are hit hardest because they all manufacture a substantial portion of vehicles (or components) in Mexico and Canada for import to the U.S. All three could lose between $5 and $9 billion each under the 25% NAFTA tariff scenario. We’re talking higher costs for engines, transmissions, or finished models like the popular Chevy Silverado (many are made in Mexico). This would reduce their profit margins or force price increases that could hurt demand. In addition, these automakers have major operations in China – especially GM, which sells more cars in China through joint ventures (like Buick and Cadillac) than in the U.S. If U.S.-China relations keep worsening, Chinese consumers or regulators might favor local brands or make life harder for foreign automakers. Indeed, we’ve seen Chinese EV companies (BYD, etc.) gain share while foreign JVs (GM and VW) lost share recently in China. Tesla’s situation we’ll mention separately. On the flip side, the Big Three benefit from protection in their home market if foreign autos are tariffed. For example, if European and Japanese cars cost 10% more, Detroit can gain some home turf advantage (though they compete more in trucks/SUVs, where foreign presence is smaller). Also, if Chinese auto imports are tariffed (say, Chinese EVs trying to enter the U.S.), that protects them too. Actually, the U.S. already had a 27.5% tariff on Chinese-made autos even before (legacy rate), so Chinese cars weren’t flooding in yet. But some Chinese EVs are coming to Europe – if U.S. prevents that, domestic makers are shielded.